With oldest grandfather in Järvsö

About Mårten Jonsson from Björs, 1838-1931 (Son-in-law in Bergmans, Kramsta)

This is a copy of a newspaper article in Ljusnan in 1928. (sent to Anders and Gunilla Björs by Ann-Helen Eriksson)

"On a hill at the top of Kramsta village, looking out over large estates and the parish's most beautiful and best countryside, there is a large farm. It has been called Bergman's for hundreds of years. It got that name when sometime in the 18th century it was acquired by a ravager by that name.

This B. must have known the ancient Egyptian advice: "Become a scribe and rule". Because either Bergman the first or some male descendant in the closest line was parish clerk and bought new properties for the farm and exchanged and moved together, what he acquired - i.a. got the captain's quarters for himself - so that he finally got 23 öres and 15 penningland of land in one ownership. It was and is a large farm according to Järvsö conditions, it had only one soldier.

Later, the farmers there were alternately called Karl Hinriksson Bergman and Hinrik Karlsson Bergman, until it happened that only girls were born in the farm and seagulls with other names, such as e.g. Markus Ersson from Mårs in Ede, came to and caused name confusion.

But before that, the farm had probably sent out into the world one, probably two, according to the old saying even. three priests with the farm's name. The Riksdagsman Karl Bergman's son Henrik Bergman is the sure one, the vicar in Färila Karl Bergman, born 1760, is the probable one. But the story tells that there was one before him.

However, it wasn't about the big farm we were going to talk about, but about grandfather there. He is the parish's oldest male resident and turns 90 on February 3 (1928).

He was not born in the farm, but became a farmer there in 1862. He was born in Stene and the son of the churchwarden Jonas Månsson, who was born in 1806 and the grandson of a soldier who moved from Funäsdalen, Måns Olsson. Ninety-year-old Mårten Jonsson's strong build is a legacy from his grandfather's home village below the sublimely magnificent Funäsdalsberget. And Mårten Jonsson is not only well-traveled, he is also unusually alert and energetic for his age.

- What is it like to be ninety years old? we asked during a visit. - Yes, you get a little cranky, replies Mårten Jonsson.

- But it seems to have been a very long time? .

- Well, not if you don't think particularly about the years. But if you do that, you think that you've been through a lot and that a lot has changed during the time you remember.

- Yes, we probably answer. And so Mårten Jonsson tells about priests and sheriffs, county councilors and judges and kinship connections endlessly, so that the whole parish seems to be one big family, a few late-comers and other railway people excepted.

- What was written in the newspaper about Jon-Ols in Sanna was wrong in many ways, he says. It said that Member of Parliament Erik Ersson was from Jon-Ers in Vik. But he was from 0l-Jons anyway. And he was not a Member of Parliament after Carl Bergman, he was before Bergman, to whom he was an uncle.

- We'll fix it, we promise.

- And the younger Erik Ersson didn't go with Ersk Jansarna (Bishop Hill) either. The Erik Janssa people went on 44, but Erik Ersson didn't go until 49. He had now almost "buzzed out" when it started. He now built a saw at Nyvallen together with Sven Olof Hultman, and it would "rain money", he thought. But it went poorly. When he left, he boasted that he would get a cut of brandy and learn English while he was on the lake. And On had enough of that - at least with the cutting - because he had to spend 11 weeks and three days on the lake. It will go faster now, remarks the 90-year-old with a twinkle in his eye.

- But can't I hear anything about what has changed, what has gone away and what has come into being during the time you remember.

- That's certainly not good. It's almost everything, that, replies the old man. Yes, the church is still standing, and it was there before I remember.

And the tåks, of course, too. But otherwise everything has changed.

- Yes, maybe, we admit.

- Yes, all the farms are rebuilt, and all the tools are changed, and all the old ways of living and working are different. Something that I remember, because they could scare us children with their hideous howling, are the wolves. Now there is not a wolf. In my childhood, in the mornings we could see trampling wolves right next to the farm, as if a "søhop" had run there. In the middle of the day, a pack of wolves could maul the dog by the yard, if he didn't manage to get in through the gate, where the wolves weren't supposed to come. And if you drove in the forest, it happened that a wolf followed for a long time. The wolves knew that dogs used to follow those who drove, and a dog was a good way to start the day. The wolves have then gone away.

It was mostly when we were in the "buan", we saw and heard wolves. At the front of the parish there were fewer of them. - Yes, almost all farmers had "bow farms" then. Two farms, and the farmstead in addition. And tools everywhere! But it was such simple furniture and household utensils, carts, plows and harrows in those days compared to now. - But there was constant moving, partly to take care of the work in all the places, partly with the livestock. In fact, people generally lived in the barn some time before Christmas. You would have to set up the crop, you got it there. It used to be a bitterly cold winter, when people came home with cows, sheep, goats and pigs. Imagine if you could now see all the animals walking in the snow! It would be a fuss then!

- And did you have hair years before?

- Yes, the worst ones were still before my memory. 37, 38 and 39 must have been the worst. But 56 and 67 were also quite difficult. In 56, father only got seed on one piece, and that was in the bow. And in 1967 I drove on the ice of Kalvsjön and Uvåssjön on May 2. It looks as if the capillaries have also disappeared.

- Surely it depends to some extent on the agricultural implements and farming methods? We suppose.

- Yes, it was thinly plowed and smooth as a floor, and the soil was as dry as ashes, if it wasn't acidic. The cover ditch was now non-existent. And in the dry soil the seed was mostly on top. The plows had a grate, which stood right out from the ridge, so that in one direction you carved, and in plows, the other direction you turned the tilt up. Iron ploughs, spring harrows, seeders and mowers, as well as threshers and wood and timber saws, lamps and iron stoves, sewing machines and separators have come to the parish within my memory. Sometime in the 50s, the first wood saw came here. It was before here in the yard a couple of Härjedal boys used it. They had bought it in Norway. And people walked a long way here and stood and watched as a wonder, as the boys stood sawing wood here. So father-in-law bought it. Yes, that saw is still here in the yard, although there is not much to it now.

- Were there really no wood saws before? we ask in surprise.

- Not here in the parish at least, answers Mårten Jonsson.

- The chipboard roofs have also come here in my memory. Skoglunds Jonas (Comminister Olof Skoglund's son) had followed his father to Tierp. And when he came back, he was going to teach them how to blow chips here. Because they had chipped roofs down in Uppland then. But there was no saw here in the parish to say off the lumps with. The residences in Kramsta, Vallmons and Stens-hammar were the first to have chipped roofs here. And now no one puts a shingle roof here.

- How was it with roads?

- Yes, there were roads. But all the country roads we now have have been built since I began to remember. In 57 and 58, the country road was built to Deisbo. Hans Mårtensson in Karsjö was the builder on it. But there was a marsh road there before. I drove it once, but it was "obsessively" bumpy and suffered and went up and down hundreds of hills. But at the front of the parish there were only bog roads.

- Drove the people to church; Didn't they mostly come by boat?

- No, it was only from Karsjö that they came on boats. They had two large boats, "Kinna" and "Kalven", with many oars. Otherwise they drove. But in the winter, when there was good ice, they skated to church. They went all the way from Kalv and Nor and Karsjö to our church, but they skated from here and to Undersvik and Arbrå to the "tar" as well. I have done that. It was so fashionable to skate for a time. And it was fun. We sit for a moment in silent contemplation of how almost everything has disappeared and everything came into being under the eyes of the 90-year-old man, so that almost only the church remains of what was before him. But the church was also different. The copper doors were open before the start of the service, and were closed during the sermon, it was sometimes 20 to 30 degrees cold inside the Lord's temple, where one could only sit during a long sermon without freezing with the help of furs and patchwork shoes.

- You must have had many assignments for the parish in the days of your power? we finally ask.

- Yes, answers Mårten Jonsson, I have now been a six-man and a twelve-man and a county councilman and a bit of each. But it's been a long time now.

- I was at the county council at the time, the provost Landgren in Delsbo was there. But I was the youngest in the county council.

This and much else interesting, e.g. about the lost market trips, when you drove by horse to Stockholm and Uppsala, about the rafting in the river, the f.n. the largest transport through the parish, about the sawmill movement, the paper-pulp industry and ore exports, about the Riksdag, social democracy and universal suffrage and finally about electricity, the telephone, cars, flying machines and the wireless, which all came to be, since he began to remember, touched the 90-year-old . But we fear that we tire our readers more than we tired the old man in half an hour. For him, life was interesting, even though you didn't seem to be able to figure out where it was going. What will the 90-year-old who is a child today have to see disappear and arise?

And we reflected on how Snoilsky was put on the back foot when he wrote: "A hundred brave German hearts are broken, but the pot still remains".

In our time, man himself survives his pots. It is true that at that moment a blasphemous thought about the pot within us came over us which is perhaps more lasting than anything, but we have no reason to concern ourselves with it right now and in the company of the quick and eloquent 90-year-old.

We thank the 90-year-old and wish him many more years of life with the same good health and unimpaired five senses. Because he sees and hears as well as a forty-year-old.

But has smiles skeptically, when he thanks.

- A long life yet, when one has reached ninety, is nothing to ask for.

S. E. & 0."

Transcript March 1984

A-H Eriksson

Handwritten comments on the transcript:

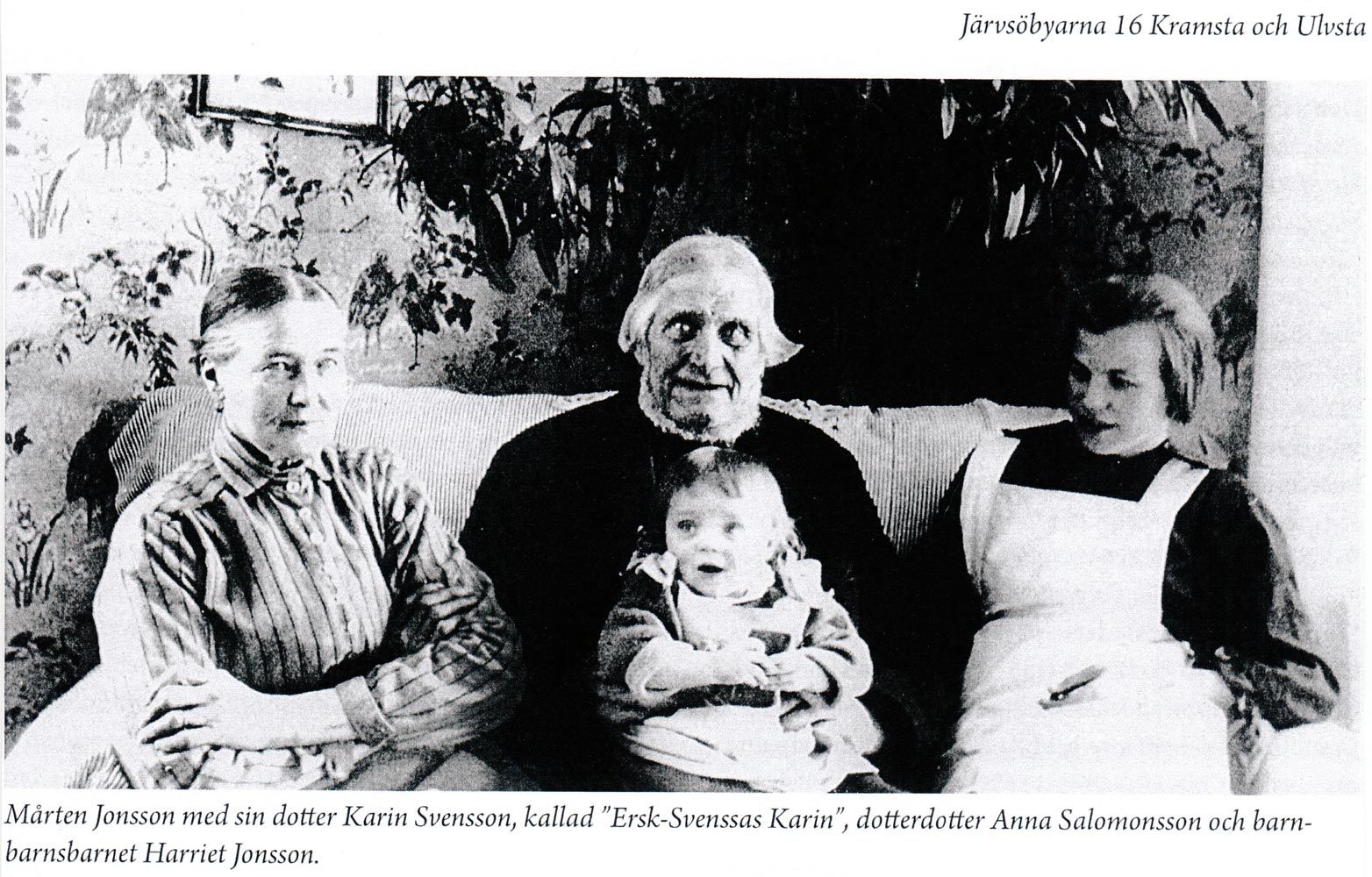

Mårten's eldest daughter Karin 1863-1945

Had a daughter Anna, born in 1903 who

had a daughter named Harriet, born in 1922 who

had a daughter Ann-Helen (nee Eriksson), born 1955

Ann-Helen has told that when Mårten proposed to Bergmans, he planted a pine tree by the Lilla Älvbron between Storsida and Kyrkön.